Treibhausgasproduzenten

10/21

MALTE WOYDT |

HOME:

PRIVATHOME:

LESE- UND NOTIZBUCH |

|

“Privilegierte, die glauben, sie kämen zu kurz”.

aus: Robert Pausch und Bernd Ulrich: Das Leuchten der Ampel, Zeit-Online, 29.9.21, im Internet.

Abb.: FDP-Wahlplakat 2013, im Internet.

09/21

“… At the age of 13, after prep school, Cameron and Johnson progressed to Eton. I went on to Radley College near Oxford. The exact school picked out by the parents didn’t really matter, because the experience was designed to produce a shared mindset. They were paying for a similar upbringing with a similar intended result: to establish our credentials for the top jobs in the country. …

It is noticeable, and often noticed, that something immature and boyish survives in men like Cameron and Johnson as adults. They can never quite carry off the role of grownup, or shake a suspicion that they remain fans of escapades without consequences. They look confident of not being caught, or not being punished if they are. …

One of the first things we learned – or felt – at prep school was a deep, emotional austerity, starting from the moment the parents drove away. … We lost everything – parents, pets, toys, younger siblings – and we could cry if we liked but no one would help us. So that later in life, when we saw other people cry, we felt no great need to go to their aid. The sad and the weak were wrong to show their distress, and we learned to despise the children who blubbed for their mummies. The cure was to stop crying and forget that life beyond the dormitories and classrooms existed. Concentrate instead on the games pitches and the dining hall and the headmaster’s study. By force of will, we made ourselves complicit in a collective narrowing of vision. …

This wasn’t healthy. In her 2015 book, Boarding School Syndrome, psychoanalyst Joy Schaverien describes a condition now sufficiently recognised to merit therapy groups and an emergent academic literature. The symptoms are wide-ranging but include, ingrained from an early age, emotional detachment and dissociation, cynicism, exceptionalism, defensive arrogance, offensive arrogance, cliquism, compartmentalisation, guilt, grief, denial, strategic emotional misdirection and stiff-lipped stoicism. …

We adapted to survive. We postured and lied, whatever it took. Abandoned, alone, England’s future leaders needed to fit in whatever the cost, and we were not needy, no sir. We could live without, and we convinced ourselves early that we had no great need of love, in either direction. Acting like a grownup meant needing no one.

Discouraged from crying out for help, frightened of complaining or sneaking, we developed a gangster loyalty to self-contained cliques, scared to death of being cast out as we had been from home. …

From the teachers, we learned about mockery and sarcasm as techniques for social control … George Orwell, during his time at prep school, remembers being ridiculed out of an interest in butterflies. The banter that day must have been immense. Nothing was sacred, and once we found out what another boy took most seriously we were ready to strike, when necessary, at its core. Our most effective defence was therefore to act as if we took nothing very seriously at all. We learned to stay detached …

At school, we tried not to feel foolish, angry, loving, stupid, sad, dependent, excited or demanding. We were made wary of feeling, full stop. By comparison, children not blessed with a private education must be fizzing with uncontrolled emotions and therefore insufferably weak. … – in the documentary Public School the boys casually refer to ‘the lower orders’, as if to a species difference, reptiles considering insects. In our isolation, we learned that we were special. Everyone else was less special and often stupid – school was where we went, aged eight, to learn to despise other people. … As Orwell doubles-down in Nineteen Eighty-Four: ‘The proles are not human beings.’ … We laughed at anyone not like us … later making us insensitive as witnesses to all but the most vicious instances of discrimination. Everyone who was not us, a boy at a private boarding school from the late 70s to the early 80s, was beneath us. …

In earlier generations, Orwell and others like him were exposed by war and other calamities to a seriousness that grew their stunted selves and tempered the isolated and ironic cult of an English private education. They were goaded by events into compassion, so that sooner or later, Orwell believed, even in ‘a land of snobbery and privilege, ruled largely by the old and silly’, England would brush aside the obvious injustice of the public schools.

The wait goes on. …”

aus: Richard Beard: Why public schoolboys like me and Boris Johnson aren’t fit to run our country. The Guardian Online, 8.8.21, im Internet.

08/21

“Last year, ‘Asian values’ became the one-stop explanation for the success of countries such as China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and Vietnam in controlling the virus. The west, many insisted, had paid for its individualist ethos by having populations refuse to obey the authorities, fail to wear masks or observe lockdowns.

Except that it has not quite turned out like that. … Tokyo is in its fourth lockdown and Covid cases are still rising sharply. … Less than a third of the population has been vaccinated and only a minority trust Covid vaccines. The only other nation so sceptical of vaccines is another east Asian country, South Korea. … All this puts a dent in the claim that Asian countries are particularly trusting of authority and exhibit a herd-like obedience.

Meanwhile, in Britain, 96% trust Covid vaccines. The supposedly highly individualist population has throughout the pandemic desired more restrictions than the government imposed. … Such attitudes are not peculiar to Britain. At the beginning of the pandemic, most European nations were highly supportive of lockdowns and other restrictions on personal freedoms, much to the surprise of the authorities. Trust in vaccines has increased in most European nations, including in France where, for historical reasons, there has been greater hesitancy. …

Far from there being a simple east/west divide, the global picture is messy in terms of attitudes, policy and outcomes. East Asian countries have disappointingly low vaccination rates, but the numbers of Covid deaths also remain low. Britain has a very high proportion of vaccinated people, but the numbers of deaths are very high …

This messiness reflects the fact that both responses to Covid-19 and the outcomes are the products of many factors. One reason many east Asian states were initially better prepared for Covid was their recent experience of similar diseases, especially Sars. …

Much of this complexity gets ignored in the drive to look for simple categories through which to view people and events and for simple divisions with which to explain the world. Many cultural developments in east Asian countries, from Seoul’s club scene to Japanese subcultures, belie the ‘conformist’ tag. Or consider that in comparing China and Taiwan the fact that one is authoritarian and the other democratic matters more than the fact that both have Confucian traditions. Ignoring that distinction allows many to portray authoritarianism as Confucianism. Nor is Confucianism the only philosophy in east Asian countries – it is simply the one with which western observers are most familiar.

Similarly, the idea that one can simply distil ‘western values‘ into individualism is as misleading as imagining that ‘eastern values’ are synonymous with conformity. …

Perhaps the most depressing consequence of the east/west myth is the belief that one can have only one or the other: that one can either be socially minded or believe in individual freedoms. The fallout from this kind of zero-sum thinking has been the distortion of ideas both of freedom and of social-mindedness. On the one hand, ideas of freedom and rights have been increasingly associated with the right and trivialised. When the refusal to wear a mask becomes seen as a heroic celebration of individualism, there is something deeply confused about the notion. Meanwhile, many sections of the left seem to have forgotten the importance of freedom to those who least possess it and have come to view community-mindedness as the imposition of greater restrictions.

There are clearly cultural differences between nations, but to frame such differences in terms of ‘east v west’ is to ignore the reality. If the pandemic has revealed anything about values, it is that east and west are still struggling to work through the relationship between individualism and community-mindedness.”

aus: Kenan Malik: Can Covid death rates be reduced to a clash of values? It’s not so simple. The Guardian Online, 8.8.21, im Internet.

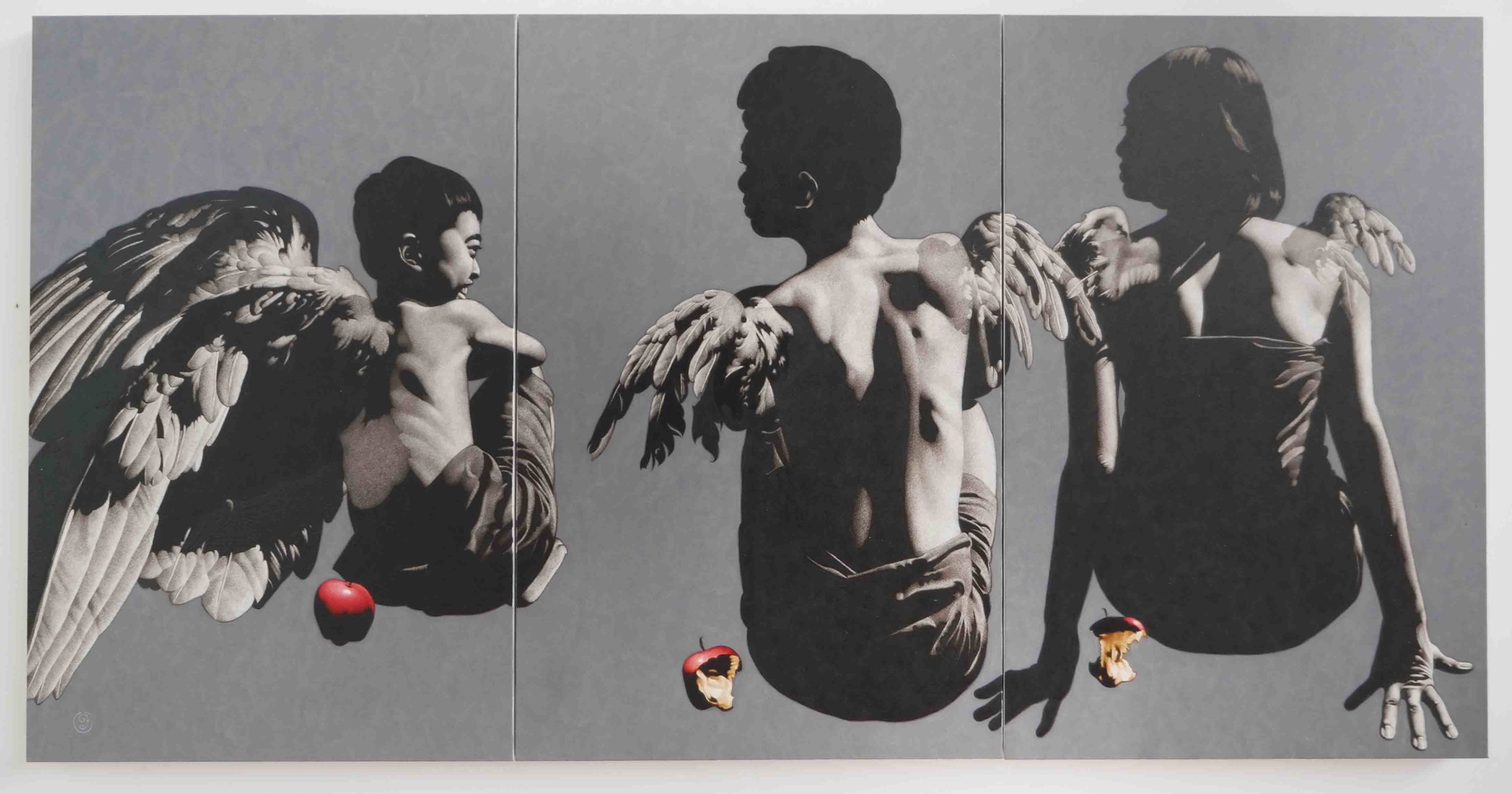

Abb.: Nguyen Tran Nam: We never fell, 2010, Nha San Collective, Vietnam, im Internet.

08/21

“Ironisch genoeg heeft het tijdperk van de vrije markt geleid tot de succesvolste afscheidingsstrijd die ooit in India gevoerd is – de afscheiding van de middenklasse en bovenlaag van de bevolking naar een eigen land, ergens hoog in de stratosfeer, waar ze opgaan in de elite van de rest van de wereld. Dit koninkrijk in de lucht is een universum op zich en is hermetisch afgesloten van de rest van India. Het heeft zijn eigen kranten, films, televisieprogramma’s, moraliteiten, transportsystemen, winkelcentra en intellectuelen. …

Maar er is één probleem: lebensraum. Een koninkrijk heeft lebensraum nodig. Waar vindt dit koninkrijk in de lucht zijn lebensraum? De burgers kijken naar beneden, naar het oude land. Ze zien adivasi’s wonen op de bauxietbergen van Orissa, op het ijzererts in Jharkand en Chhattisgarh. Ze zien in Nandigram mensen (moslims en dalits) wonen op toplocaties waar eigenlijk chemische fabrieken zouden moeten staan. … Ze denken: dat is ons bauxiet, ons ijzererts, ons uranium. Wat doen die mensen op ons land? Wat doet ons water in hun rivieren? Wat doet ons hout aan hun bomen?

… Wanneer de burgers van het koninkrijk in de lucht hun blik over het land laten gaan, zien ze overbodige mensen die op kostbare bronnen wonen. De nazi’s hadden een benaming voor ze: überzählige Esser, overtollige eters. …

Historisch gezien is efficiëntste vorm van genocide: mensen uit hun huis halen, ze bijeendrijven en water en voedsel ontzeggen … Mogelijk op China na heeft India nu de grootste populatie ontheemden ter wereld. Alleen al door de aanleg van dammen zijn meer dan dertig miljoen mensen verdreven. …

Het kunstmatige universum … vertelt ons dat de rijken geen keuze hebben (er is geen alternatief) maar de armen wel. Die kunnen ervoor kiezen om rijk te worden. Doen ze dat niet, dan verkiezen ze pessimisme boven optimisme, aarzeling boven zelfvertrouwen, gebrek boven hoop. Met andere woorden: ze kiezen ervoor om arm te zijn. Het is hun eigen schuld. Ze zijn zwak. (En we weten hoe zoekers naar lebensraum over zwakken denken.) Ze zijn ‘de spoken uit het verleden die mensen gevangenhouden’. Ze zijn nu al spoken. …

Misschien vragen deze miljoenen mensen ‘spoken uit het verleden’ zich af welk advies Gandhi zou gegeven hebben … Misschien vragen ze zich af of ze in hongerstaking kunnen gaan, hoewel ze al bijna omkomen van de honger. Of ze buitenlandse goederen kunnen boycotten, hoewel ze geen geld hebben om die goederen te kopen. Of ze kunnen weigeren om belasting te betalen, hoewel ze geen inkomsten hebben.

Mensen die de wapens hebben opgenomen weten heel goed wat de gevolgen van een dergelijke beslissing zijn. … Honderdduizenden hebben het vertrouwen in de instituten van de Indiase democratie opgezegd. Grote delen van het land hebben zich onttrokken aan het gezag van de regering. (Bij de laatste telling naar verluidt vijfentwintig procent.) De strijd stinkt naar dood en verderf. … Mensen geloven dat wanneer er gedreigd wordt met vernietiging, ze recht hebben om terug te vechten. Met alle mogelijke middelen. …”

aus: Arundhati Roy: redevoering, gehouden op 18 januari 2008 in Istanboel, een jaar na de moord op Hrant Dink, redacteur van de Turks-Armeense krant Argos. Veröffentlicht in Outlook (India), 4.2.8. Hier in: dies.: Luisteren naar Sprinkhanen, aantekeningen over democratie. Amsterdam: De bezige bij, 2010, S.183-191

Abb.: Amol K Patil, Sweep Walking, 2015, installation detail. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, im Internet.

07/21

“There is a simple reason why Boris Johnson and European leaders failed to find common ground over Brexit at last week’s G7 summit. They are not even talking about the same thing.

For the British prime minister, Brexit is a matter of national character that cannot be described in legal documents. For continental politicians, legal texts contain the true meaning of a project that only exists in the real world as a set of rules to be implemented. To Johnson, the withdrawal agreement was a single-use tool for levering himself out of a tight spot. For Brussels, it is the chamber into which Britain levered itself.

That difference will continue to cause friction because it is not a misunderstanding. Johnson knows that legal arguments over the Northern Ireland protocol favour the European position. He chooses not to care. To concede on the principle that any part of the UK is subject to European regulatory standards – the compromise he signed to avoid a land border on the island of Ireland – would be to admit that a portion of sovereignty was conceded in the negotiations.

That would be a stain on his self-image as the man who made a clean break from Brussels. He finds confrontation more appealing, not least because he expects it to achieve more than compliance. Whether that is true depends on how you define achievement.

Johnson’s calculation doesn’t prioritise peace in Northern Ireland. … If Northern Ireland is on fire, any insistence from Brussels on maximum implementation of rules on sausage imports will look callous and disproportionate. …

That technique will not do much for Britain’s reputation abroad, but Johnson’s mind rarely strays far from his domestic audience, to whom he will explain that everything is the EU’s fault. His party and most of the media will endorse that interpretation, as it always has done. …

When Johnson’s critics say he must be held accountable for Brexit, they use that word to mean the process and cost of severing ties with Britain’s neighbours and losing frictionless access to their markets. That is the remainer definition, even when used by people who accept there is no remain cause left to fight. When Tories say “Brexit” they mean it in the wider sense of a cultural revolution, sustained by belief and national pride. … The project’s goals are too abstract to be attainable in any economically useful sense – there are no new jobs in the sovereignty-manufacturing sector – so momentum is maintained by always reimagining and refighting the old enemy. …

This is the long tail of Brexitism – a political mode that has its genesis in the referendum but has evolved into something much wider. Its defining feature is the flight from complex reality to symbols and fantasy. …

Theresa May was broken by the attempt to divert the frothing stream of leaver demands down narrow channels of responsible statecraft. Her successor declared such restraint unnecessary, and then appeared to prove the point by getting a Brexit deal done. The trick was to sign the treaty without intending to honour it.

All who serve in the current cabinet have signed up to the Johnsonian code of conduct that makes evidence and truth subordinate to the performance of boosterism. … Real-world government is a sequence of arguments over what is available on current budgets and, if more cash is needed, who will pay. …

Brexit is not really a destination but a state of mind. It is not something that government can do, but a way of deferring all the things government should be doing but would rather not contemplate. …”

aus: Rafael Behr: British politics is still drunk on Brexit spirit, and Boris Johnson won’t call time. The Guardian Online, 16.06.2021, im Internet

06/21

“… die Lebenserfahrung der Sowjetbürger [stellt] jede marxistische Klassenanalyse in den Schatten … Die Menschen in diesem Land sind mit den feinsten Nuancen von Status, Rang und Lebensstandard vertraut, und das betrifft keineswegs nur die Wohnungsfrage. Wer kann über ein eigenes Telephon verfügen? Wohin, wenn überhaupt, fährt er in Ferien? Welche Papiere hat er, und welche fehlen ihm? Wohin geht er, wenn er krank ist? In welchen Läden kauft er ein? Wohin kann er reisen, wohin nicht? Wie zieht er sich an? Wo studiert er, und was? Welche Schuhe trägt er? Was ißt er? Hat er eine Datscha? …”

aus: Hans-Magnus Enzensberger: Tumult. Berlin: Suhrkamp 2014, S.81.

Abb.: Ion Bârlădeanu: Untitled, 1988, im Internet.

05/21

“Das Paradies der Muslime verspricht den Gläubigen, was die Wirklichkeit ihnen verweigert: grüne Auen statt der Sandwüste; schöne Huris statt unerreichbarer Frauen und Homosexualität aus Not; reiche Speisen, die sich in Luft auflösen, statt mit Ruhr oder Cholera zu drohen. Dieses Paradies folgt … einer stringenten Logik.

Das Christentum kennt zwei Paradiese, die seltsam miteinander konkurrieren. Der Garten Eden entspringt einer orientalischen Phantasie. Er ist sinnlich und wird anschaulich beschrieben: üppige Vegetation, Versöhnung mit der Natur, die Menschen sind nackt, sie arbeiten nicht. Dagegen liegt über dem himmlischen Paradies der reinen Lehre ein Bilderverbot, das die Phantasie lähmt und bloß ewige Langeweile verheißt. Die Angst vor der Hölle war in Europa immer stärker als die Lust auf eine solche Belohnung. …

Mich hat früher der Garten Eden skandalisiert. Als Kind schien es mir, als verdiene ein Paradies seinen Namen nicht, auf dem Schilder aufgestellt seien wie … ‘Äpfel essen verboten’. Heute denke ich anders darüber; denn mit dem Verbot war den Bewohnern des Gartens die Freiheit und die Zeit geschenkt – die Zeit vorher und die Zeit danach. Der Apfel war der größte Genuß, den der Garten zu bieten hatte. Er gab die Falltür, den Notausgang frei, versprach den Eros und die Intelligenz. Ohne die verbotene Frucht wäre dieser Ort ein Gefängnis gewesen. Von einem Paradies ist zu fordern, daß man es verlassen kann, wenn man genug davon hat. Das gilt auch für politische Paradiese, wie sie der Kommunismus versprach.”

aus: Hans-Magnus Enzensberger: Tumult. Berlin: Suhrkamp 2014, S.265/266.

Abb.: Sugio: Threesome, 2018, indoartnow, im Internet.

05/21

“Zu meiner Überraschung zeigte sich, daß unser wütendes Land ganz allmählich, fast hinter unserem Rücken, immer bewohnbarer wurde. Niemand schlug mehr die Hacken zusammen, niemand machte einen Diener, Autofahrer fingen an, Fußgänger an der Kreuzung passieren zu lassen, Polizisten warfen ihre Tschakos ab, Busschaffner warteten auf alte Damen, statt ihnen vor der Nase wegzufahren. Der Kuppelparagraph und der §175 wurden abgeschafft. Gegen den hinhaltenden Widerstand des Obrigkeitsstaates setzten sich lässige Verkehrsformen durch. Es geschahen Zeichen und Wunder in Deutschland. Man konnte den Eindruck haben, als wäre die Republik auf dem Weg zur Zivilisation. …

Die Systemopposition ist … zum bloßen Relais der Modernisierung geworden. Sie hat den Lernprozeß der kapitalistischen Gesellschaft entschiedener vorangetrieben als ihre Verteidiger …”

aus: Hans-Magnus Enzensberger: Tumult. Berlin: Suhrkamp 2014, S.243 und 269

05/21

“Part of the English disease is our readiness to ascribe our national disasters to questions of personal character. But the vanities of posh men and their habit of dragging us into catastrophe have much deeper roots. They centre on an ancient system that trains a narrow caste of people to run our affairs, but also ensures they have almost none of the attributes actually required.”

aus: John Harris: Britain’s overgrown Eton schoolboys have turned the country into their playground. The Guardian online, 2.5.21, im Internet.

05/21