“What will be remembered about the twenty-first century more than anything else, except perhaps the effects of a changing climate, is the great, and final, shift of human populations out of rural, agricultural life and into cities. We will end this century as a wholly urban species. … it will be the last human movement of this size and scope. [S. 1] …

In my journalistic travels, I developed the habit of introducing myself to new cities by riding subway and tram routes to the end of the line, or into the hidden interstices and inaccessible corners of the urban core. … These are always fascinating, bustling, unattractive, improvised, difficult places, full of new people and big plans. [S. 2] …

This ex-rural population, I found, was creating strikingly similar urban spaces all over the world: spaces whose physical appearance varied but whose basic set of functions, whose network of human relationships, was distinct and identifiable. And there was a contiguous, standardized pattern of institutions, customs, conflicts and frustrations being build and felt in these places [S. 3] …

The great migration of humans is manifesting itself in the creation of a special kind of urban place. These transitional spaces – arrival cities – are the places where the next great economic and cultural boom will be born, or where the next great explosion of violence will occur. The difference depends on our ability to notice, and our willingness to engage. [S. 3] …

Tower Hamlets, London, UK … The easy ability to open a small business in Britain, to get credit and purchase property and obtain restaurant licences without prejudice, allowed the Bangladeshis to avoid destitution and dependency, to accumulate capital and provide legitimate employment to new arrivals as British immigration laws toughened, and to build futures for their children over the hot tandoori ovens. Small businesses of this sort are the heart of almost any successful arrival city, and their absence, or the presence of laws that keep immigrants from opening them, is often the factor that turns arrival cities into poverty traps. [S. 28/29] …

Around the world, it appears that a good part of the success or failure of an arrival city has to do with its physical form – the layout of streets and buildings, the transportation links to the economic and cultural core of the city, the direct access to the street from buildings, the proximity to schools, health centres and social services, the existence of a sufficiently high density of housing, the presence of parks and neutral public spaces, the ability to open a shop on the ground floor and add rooms to your dwelling. [S. 32/33] …

The informal economy, previously considered a parasitic irrelevance on the edge of the “main” industrial economy, now represents a quarter of all jobs in post-communist countries, a third in North Africa, half in Latin America, 70 per cent in India, and more than 90 per cent in the poorest African countries. [S. 41] …

Kamrangirchar, Dhaka, Bangladesh … Jamar is the cable-TV man. This makes him a powerful and influential figure in the new slum, in good part because his is the first and most reliable utility to be delivered, years or decades ahead of running water, postal services and sewage. All across the developing world, in South America and Asia and the Middle East, the cable guy has become a source of influence in the slum. … To walk through the slum at night is to traverse pools of blue light and competing blasts of tinny music. [S. 48/49] … Poor people move house frequently, and arrival cities, in their early years, are places of constant movement and change. [S. 50/51] … In Bangladesh, as in many other places, the arrival city is turning women into primary headwinners, and they play a prominent and visible role in these communities. [S. 51] … As everywhere, life is a bet on the future of the children. Arrival cities are places of generational deferral, in which entire lives are sacrificed, often in appalling conditions, for a child’s better opportunity. [S. 52/53] …

In the earliest decades of the great arrival city boom, from the 1940s to the 1970s, the predominant way to acquire land was by squatting. … But the land invasion has become a much rarer activity … First, land nowadays tends to be private, with clear owners … Second, rural migrants, almost universally, do not want ambiguity in their possession of the land beneath their feet: the want clear ownership. [S. 54] …

Los Angeles, California … In the decade after Los Angeles burned, swathes of the city’s core turned from poor neighbourhoods populated by black tenants who rented from absentee white landlords into Latino arrival cities whose residents struggled to buy their ghetto homes. … While poor black Angelos were struggling to escape their neighbourhood as fast as they could and move into the suburbs, as the white working class had done a generation before, the Spanish-speaking arrivals were struggling to dig in, buy their homes and set up a shop. [S. 79] … People move through its neighbourhoods. … They arrive very poor, with poverty rates approaching 25 per cent, but … these rates fall sharply, especially during the first decade of residence, generally to less than 10 per cent. Nevertheless, the neighbourhoods themselves often stay poor or even get poorer. … The American arrival city … is constantly sending its educated second generation into more prosperous neighbourhoods and taking in waves of new villagers … the neighbourhood itself appears poorer than it really is. … [S. 82]

Parla, Spain. …A major study found that the Spanish-born children of Moroccan immigrants are becoming fully integrated into Spanish language and customs far better than South American and Central American migrants to Spain … This difference is attributed to the fact that Spanish immigration policies for Morrocans and other Africans, which were formulated a decade later, made is possible for entire families to migrate and become citizens, so that children are not raised in single-parent families or in families assembled through immigration-driven forced marriages. The Latin-American migrant process was more likely to split up families. [S. 259/260] …

Bijlmermeer [Amsterdam] … was subject … to what has been described as the most dramatic and violent act of arrival-city transformation in modern history. Build in the late 1960s …, it was a huge honeycomb of 31 very wide 10-storey apartment towers with wide spaces between them, housing 60,000 people in a commerce-free expanse of parkland and public spaces, separated from the city by a greenbelt. It never really even began to succeed …, having only a 20 per cent Dutch-born population. … Bijlmermeer was often described in the 1970s and early 1980s as the most dangerous neighbourhood in Europe. …

Finally, beginning in the mid-1990s … Amsterdam demolished all the apartment towers in two waves and replaced them with a tighter arrangement of mid-height structures that gave each apartment its own garden and ‘ownership’ of a section of the street, with loosely zoned spares for shops and businesses in between, allowing teeming and haphazard markets. This decade-long job was accompanied by a new active government role in the city’s southeast; its cornerstones are a powerful local security patrol and a municipal corporation dedicated to providing support to entrepreneurs and job-related training to youth. A new Metro link to the neighbourhood flowered into a prosperous business end entertainment hub. … What is it that the Dutch are doing with their arrival cities? First, they are increasing their intensity. … Until very recently, most urban officials believed that the greatest threat to the poor was crowding, density and confusion. … In less-desirable neighbourhoods, the poor arrivals are stuck with low intensity, high-division planning that forbids spontaneity. … [S. 297]

Around the world there is confusion about what should best be done about these neighbourhoods. [S. 306] … Often, the size of the building makes the difference, and there is a reason, why poor neighbourhoods in the developing world, when they turn into more prosperous neighbourhoods, so often evolve into long rows of five-storey buildings with shops on the ground floor. This is an almost ideal arrangement for self-managed neighbourhoods … People who arrive in cities need the help of the state. And what arrival cities need most – and what the market will almost never provide – are the tools to become normal urban communities. Sewage, garbage collection and paved roads are, for obvious reasons, vital and can be provided only from outside. But even more important, in the well-informed view of slum-dwellers, are buses: affordable and regular bus service into the neighbourhood is often the key difference between a thriving enclave and a destitute ghetto. One might think that the next priority would be electricity and running water, but in fact, these are often not considered priorities at all by slum-dwellers. They have typically arranged their own utilities, , and full-price utilities can be debilitating for poor households. Equally important, and far too often neglected, is street lighting. [S. 309-311]. …

… ethnic clustering (some would say segregation) gave the arrivals the benefit of ‘differential citizenship’ allowing them to participate in what I have described as a culture of transition. [S. 317].”

aus: Doug Saunders: Arrival City. How the largest migration in history is reshaping our world. London: Windmill 2010.

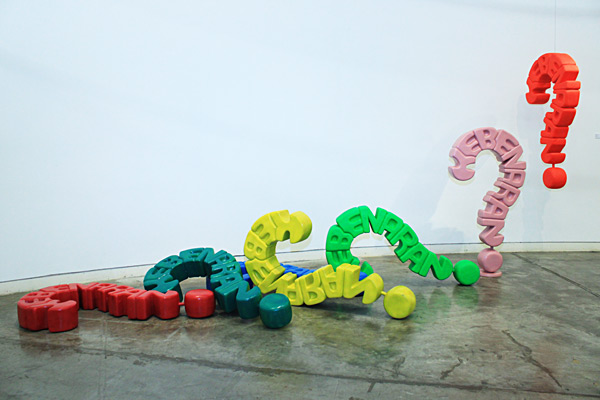

Abb.: Michael Cook: Sold (Livin’ the Dream Series), 2020. im Internet.

06/14