Blacks

“Je n’aime pas les Blacks, tout d’abord parce que nous sommes en France, et qu’en France on parle français. C’est bien la moindre des choses.

La blackitude est un produit qui a trois sources principales. La première est sociolinguistique et c’est que j’appelle les édulcorations coupables. La deuxième est le fruit du rejet dont ceux qu’on nomme les Blacks se sentent victimes. La troisième, c’est en référence aux USA. …

[1] Les hommes de race dite noire sont des négroïdes. Leur véritable appellation devrait donc être Nègre. Dans tous les cas, c’est l’appellation originale. Cette appellation a été utilisée pendant des siècles et jusqu’au lendemain de la traite. Mais après la traite … le mot Nègre est devenu péjoratif. …

Pendant la colonisation, le Nègre est devenu Noir. Je ne sais s’il a gagné à ce changement, d’identité. Mais l’assimilation de tout ce qui est mauvais à la couleur noire me pousse à croire qu’il s’agit plutôt d’une régression. …

Aujourd’hui, le mot Noir est aussi devenu une insulte. …

[Ces] édulcorations linguistiques renvoient au sentiment de culpabilité que ressent l’homme blanc envers les peuples qu’il ne cesse de soumettre ou d’exploiter. Elle est tout aussi pathétique pour le Blanc qu’injurieuse pour le Noir, cette tentative de gommer l’histoire sans en subir l’exorcisme, sans en réparer les dégâts, en refusant d’affronter ses mauvais actes comme la colonisation, l’esclavage, la ségrégation raciale, de penser qu’on les gomme de l’histoire juste par une fuite en avant, juste en changeant les mots. Il est dévalorisant pour le Noir, ce recours permanent à l’amnésie collective, position que l’on trouve politiquement correcte. Si le mot Noir perd son sens négatif dans le dictionnaire, il le perdra aussi dans la perception populaire. C’est dans ce sens qu’il convient d’agir.

[2] Ces contorsions linguistiques montrent clairement que le Blanc ne considère pas ces peuples comme ces égaux. … À quoi cela sert-il de débaptiser les Nègres tous les cinquante ans si l’on ne change pas le regard que l’on pose sur eux ? Je trouve ces simagrées coupables et même humiliantes.

[3] Entre-temps l’espèce ‘black’ est apparue dans le paysage social français. Ce terme s’applique aux jeunes d’origine noire – africaine ou antillaise – qui l’ont repris entièrement à leur compte, tant et si bien que l’on pourrait se demander s’ils n’en sont pas les inventeurs. Le véritable créateur reste la société qui a mis en place depuis bien longtemps le système des euphémismes.

Si les jeunes Noirs ont repris cette appellation à leur compte, c’est parce qu’ils sont convaincus qu’ils sont rejetés et ségrégués par la société française. L’unique fondement de ce rejet est la couleur de la peau. Ils se considèrent très rarement comme africains, ivoiriens, camerounais, congolais ou encore maliens, sénégalais. Ils sont français, mais différents. La fraternité qui lie les adultes venant du même État africain – Mali, Sénégal, Cameroun, etc. – ne les concerne pas … ces enfants ne se regroupaient pas selon les origines de leurs parents. Fortement bestialisés, comme une meute, ils s’associent sur les critères d’espèce à défendre, et de territoire à protéger. …

Comme ils sont blacks, ils appartiennent à la planète black, À une internationale black dont ils savent que les membres sont rejetés dans tous les pays où ils sont en minorité, et même parfois en majorité, si l’on pense à l’Afrique du Sud de l’apartheid. Ainsi, ils tirent leurs références de ce qui leur apparait comme le paradis de la blackitude, les USA. …

Je me souviens du voyage que Kodjo … avait effectué aux USA, il y a une dizaine d’années, juste après sa majorité, avec quelques amis de quartier. … Un beau matin … ils s’embarquèrent pour New York avec pour viatique leurs rêves et leurs ambitions et la certitude de voir enfin des Noirs heureux. … Dans la rue, c’est l’horreur ! Tous les mendiants qu’ils rencontrent, ‘sauf un’, précisent-ils, sont des Noirs. Des centaines des Noirs … qui ont été détruits par l’héritage sociologique de l’esclavage, qui n’ont ni âme ni ambition, ni repères, ni diplômes, ni travail et qui passent la vie à mourir lentement. Quand nos jeunes explorateurs reviennent en France, ils se sentent plus français que jamais. …

Aujourd’hui, les Blacks continuent à être subjugués par les États-Unis, dont ils adoptent la mode des ghettos noirs, imposés par les rappeurs : bandana unicolore sur la tête, pantalons informes, immenses porte-clés-porte-médaillons. …

Le hip-hop n’est plus ce qu’il était et le basketball s’est essoufflé. Pourtant, les Blacks conservent la même rage, décuplée par l’inactivité. … Rien de plus désolant que ces enfants noirs entre cinq et dix ans, que l’on voit en grappes dans les supermarchés, les transports en commun, les places publiques, les parcs …

Pendant ce temps, la société dort en paix en parlant de Liberté, alors qu’elle prépare ces enfants à ne plus en avoir dans un avenir proche ; en parlant d’Égalité alors qu’on les prépare à être inférieurs à cause de leur déficit d’éducation : en parlant de Fraternité alors qu’on en a fait d’éternels étrangers. En effet, ils deviendront français quand vous cesserez de voir en eux des Blacks et quand ils seront redevenus des Noirs, tout simplement.”

aus: Gaston Kelman: Je suis noir et je n’aime pas le manioc. Paris: 10/18, 2005 (2004), S.120-132.

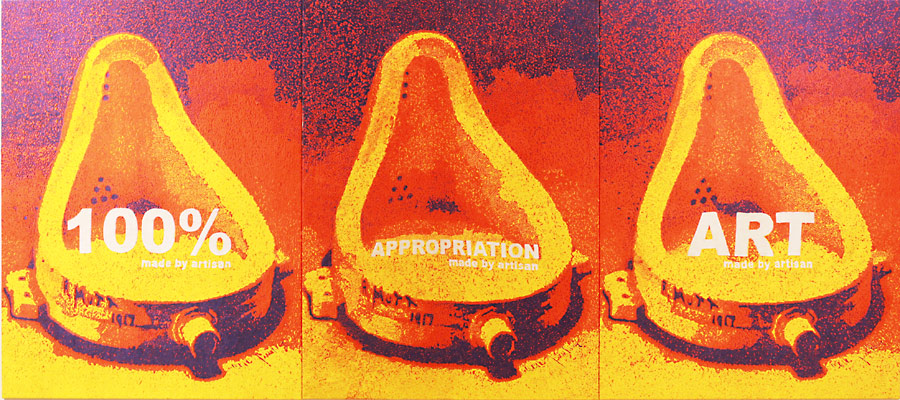

Abb.: damali ayo: Flesh tone, 2003, custom mixed house paint matching face, arms, belly, back, thigh, breast and palm. damaliayo.com.

12/21